The interplay of chess pieces on the 64-square battlefield often leads to intricate endgame scenarios that can sway the course of a game.

Among these, the concept of “Bishops of opposite colors” emerges as a fascinating and strategic element.

As players maneuver their bishops across light and dark squares, the dynamics of this situation introduce a unique dimension to endgame strategy.

In this exploration, we delve into the intricacies of bishops of opposite colors, understanding their impact on endgame outcomes, drawing tendencies, and the strategic considerations that arise when these contrasting bishops take center stage on the chessboard.

What are Bishops Of Opposite Colors?

The term “Bishops of opposite colors” refers to a specific endgame scenario in chess where each player has one bishop, but they are on opposite-colored squares. In other words, one player’s bishop is on light squares (white squares), while the other player’s bishop is on dark squares (black squares).

Bishops of Opposite Colors

This situation is particularly significant in the endgame because bishops are long-range pieces that can control squares of their own color.

When bishops are on opposite colors, they have a limited ability to directly interact or attack each other, since they are restricted to squares of different colors.

The presence of bishops of opposite colors often leads to drawish tendencies in the endgame, especially when there are few pawns or pieces remaining on the board.

This is because the bishops cannot easily target each other’s pawns or coordinate in an attack, making it difficult for one side to create significant threats against the other.

Material Advantage

In typical endgame scenarios, the side with a material advantage (extra pawns or better piece coordination) can often press for a win, as the opponent might struggle to defend against multiple weaknesses at once.

However, in bishops of opposite colored endgame, if the position is relatively balanced and there are no clear targets to attack, the game can often end in a draw due to the limited ability of the bishops to influence each other’s side of the board.

How Difficult It Is To Win with Bishops of Opposite Colors?

The endgame scenario where both players retain solely pawns and bishops of opposite colors is renowned for its complexity in securing victory.

The side with fewer resources often employs a blockade strategy on squares under the influence of its own bishop. A mere one-pawn advantage typically falls short of ensuring a win.

A favorable outcome becomes plausible when the more advantaged side possesses passed pawns on both flanks or connected passed pawns. In the latter scenario, the winning approach involves advancing pawns strategically onto squares controlled by the opposing bishop, effectively dismantling any potential blockades.

Bishop vs Bishop and Pawn

In endgame configurations of this nature, the aggressor’s bishop often finds itself rendered ineffective, while the defender usually attains a draw if their king can access a square ahead of the pawn that doesn’t share the attacking bishop’s color.

Alternatively, the defender can secure a draw if their bishop can consistently exert control over a square situated before the pawn. These particular endgame scenarios are commonly resolved into draws, with such outcomes arising approximately 99% of the time.

Bishop vs Bishop and 2 Pawns

Approximately fifty percent of these positions result in draws. In the majority of other endgames, possessing a two-pawn advantage often leads to a straightforward victory.

By way of comparison, if the bishops occupied squares of the same color, winning outcomes would manifest in around 90% of the positions.

The situations can be categorized into three broad scenarios, contingent upon the configuration of the two pawns.

Typically, a duo of interconnected pawns presents the most favorable prospects for achieving a win. However, in these particular instances, the superior winning opportunities tend to favor a pair of widely separated pawns—except when one of the pawns happens to be the incorrect rook pawn.

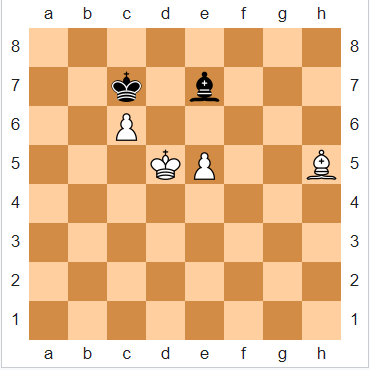

Doubled Pawns

In cases where pawns are doubled, the outcome settles into a draw provided the defending king can access a square ahead of the pawns that differs in color from the attacking bishop’s influence.

The presence of a second pawn on the same file does not alter this scenario, likening it to an ending involving just one pawn.

If the combined efforts of the defending king and bishop are insufficient to fulfill this criterion, the initial pawn will secure victory by capturing the defending bishop, while the subsequent pawn’s promotion will follow suit.

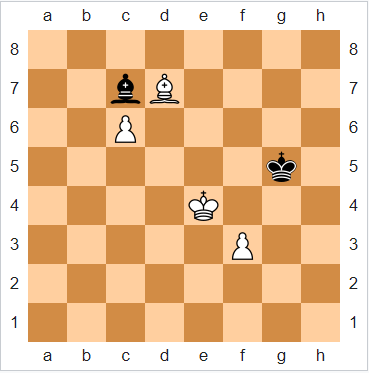

Isolated Pawns

Isolated pawns. White to play, a draw. White wins if the pawn is on f5 instead of e5.

When dealing with isolated pawns, their placement on non-adjacent files significantly influences the final outcome.

The degree of separation between the pawns becomes a pivotal factor; the wider the gap, the more favorable the prospects for victory.

A prevailing principle typically emerges: when the pawns are separated by just a single file, the result tends toward a draw; on the other hand, if there is a greater gap, the attacker usually secures the win.

This principle can be explained by the dynamics that unfold when the pawns are more widely apart. The defending king must obstruct one pawn’s progress while their bishop thwarts the other pawn.

Consequently, the attacking king can lend its support to the pawn obstructed by the bishop, ultimately capturing the defending piece.

Conversely, if there’s only one file between the pawns, the defender can effectively hinder their advancement.

If the pawns are separated by three files, victory generally favors the pawns. Nevertheless, certain positions permit the defender to establish a blockade, particularly when one of the pawns involved is the incorrect rook pawn.

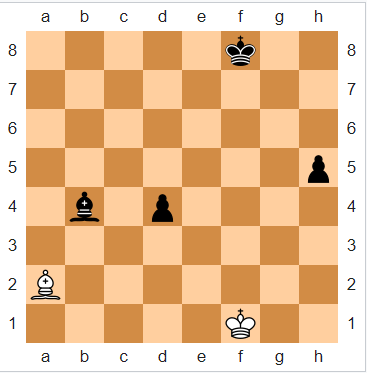

Wrong Rook Pawn

Should one of the two pawns prove to be the incorrect rook pawn, specifically an a- or h-pawn with its queening square on the opposite-colored squares from those under the influence of the superior side’s bishop, a unique defensive strategy known as a fortress can come into play.

This tactic can enable the disadvantaged side to secure a draw, regardless of the extent to which the pawns are apart.

A telling illustration of this concept is evident in the Alekhine–Ed. Lasker match held in New York City in 1924.

Despite a three-file separation between Black’s two pawns, the game concluded in a draw following 52.Bb1 Kg7 53.Kg2, as both players agreed.

Alekhine elaborated in the tournament record that White could “sacrifice his Bishop for the [d-pawn], in as much as the King has settled himself in the all-important corner.”

The crux of this scenario lies in the fact that if the wrong rook pawn is involved, the eventual outcome hinges on whether the defending king can successfully occupy the crucial corner space positioned ahead of the rook pawn.

From this strategic position, the defender can orchestrate a bishop sacrifice against the other pawn, thereby influencing the draw.

The outcome’s determinants are not the pawns’ separation or advancement but the intricate interplay of positioning and sacrifice.

Final Thoughts

As we’ve explored the dynamics of these contrasting bishops, we’ve uncovered their potential to shape endgame scenarios, influence draw tendencies, and offer players strategic avenues for victory.

While the presence of bishops of opposite colors may often lead to cautious and measured play, their intricate dance on the board showcases the profound interplay between seemingly minor pieces and the grand strategy of the game.

Mastering the art of maneuvering bishops of opposite colors demands a keen understanding of positional nuances and the ability to seize fleeting opportunities that arise in these distinctive endgame situations.

Whether producing tactical fireworks or fostering cautious maneuvering, bishops of opposite colors enrich the chess landscape and stand as a captivating testament to the timeless allure of the game.